If mouseX and mouseY are used in programs without a draw() or if noLoop() is run in setup(), the values will always be 0. If the cursor is at the top, the mouseY value is 0 and the value increases as the cursor moves down. If the cursor is at the left, the mouseX value is 0 and the value increases as the cursor moves to the right. If the cursor moves into the display window, the values are set to the current position of the cursor. When a program starts, the mouseX and mouseY values are 0. Println(str(mouseX) + " : " + str(mouseY))

To see the actual values produced while moving the mouse, run this program to print the values to the console: The Processing variables mouseX and mouseY (note the capital X and Y) store the x-coordinate and y-coordinate of the cursor relative to the origin in the upper-left corner of the display window.

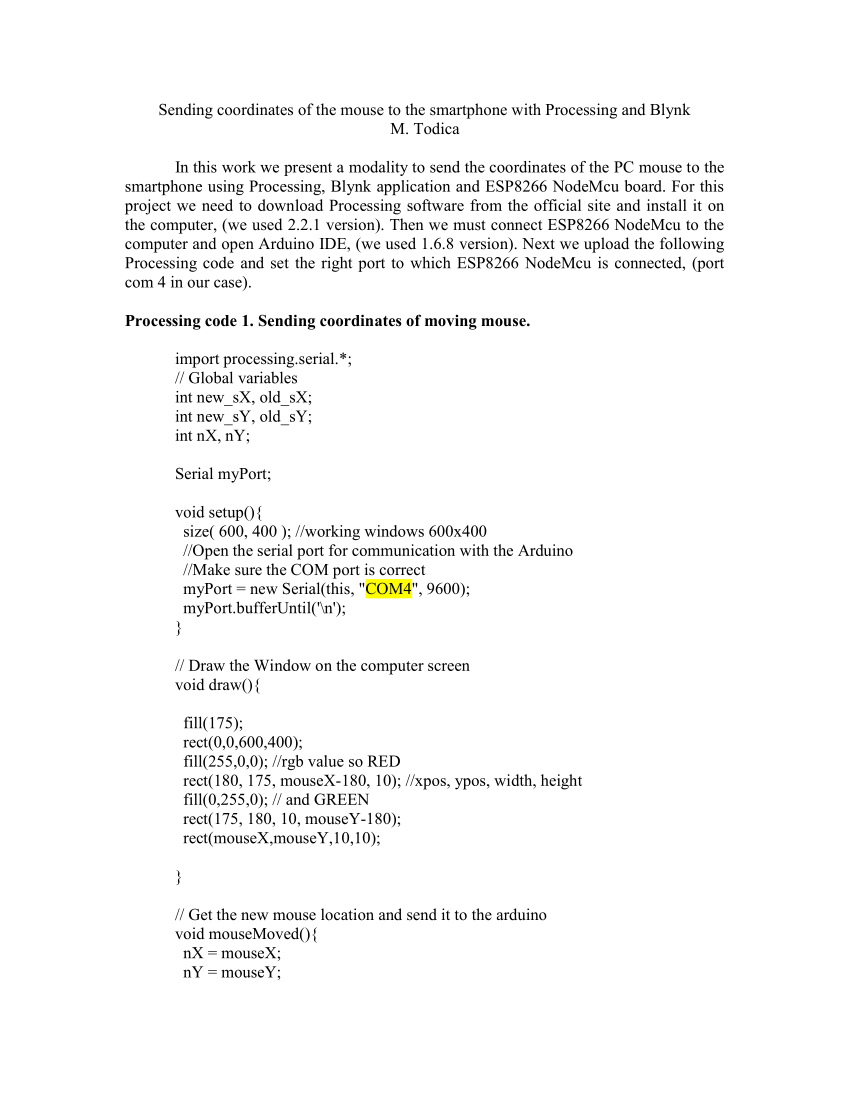

#PROCESSING MOUSE COORDINATES SOFTWARE#

This more than one-hundred-year-old mechanical legacy still affects how we write software today. It was developed for typewriters to put physical distance between frequently typed letter pairs, helping reduce the likelihood of the typebars colliding and jamming as they hit the ribbon. This layout is called QWERTY because of the order of the top row of letter keys. The position of the keys on an English-language keyboard is inherited from early typewriters. The modern computer keyboard is a direct descendant of the typewriter. It's also possible to ignore the characters printed on the keyboard itself and use the location of each key relative to the keyboard grid as a numeric position. This information could control the speed of an event or the quality of motion. For example, basic information such as the speed and rhythm of the fingers can be determined by the rate at which keys are pressed. When writing your own software, you have the freedom to use the keyboard data any way you wish. The migration of the keyboard from typewriter to computer expanded its function to enable launching software, moving through the menus of software applications, and navigating 3D environments in games. Keyboards are typically used to input characters for composing documents, email, and instant messages, but the keyboard has potential for use beyond its original This data can in turn be used for gesture and pattern recognition. If these coordinates are collected andĪnalyzed, they can be used to extract higher-level information such as the speed and direction of the mouse. These numbers can be used to control attributes of elements on screen. The cursor position is read by computer programs as two numbers, the x-coordinate and the y-coordinate. The physical mouse object is used to control the position of the cursor on screen and to select interface elements. In Engelbart's original patent application in 1970 he referred to the mouse as an "X-Y position indicator," and this still accurately, but dryly, defines its contemporary use. The design of the mouse has gone through many revisions in the last forty years, but its function has remained the same. The mouse concept was further developed at the Xerox Palo Alto Research Center (PARC), but its introduction with the Apple Macintosh in 1984 was the catalyst for its current ubiquity. The computer mouse dates back to the late 1960s, when Douglas Engelbart presented the device as an element of the oN-Line System (NLS), one of the first computer systems with a video display. We control elements on screen through a variety of devices such as touch pads, trackballs, and joysticks, but the keyboard and mouse remain the most common input devices for desktop computers.

The screen forms a bridge between our bodies and the realm of circuits and electricity inside computers. If you see any errors or have comments, please let us know. This tutorial is for Processing version 2.0+ and has been adapted for Python Mode. This is the Interactivity chapter from the second edition of Processing: A Programming Handbook for Visual Designers and Artists, published by MIT Press.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)